Truth and reconciliation commissions attempt to heal divided nations after the injustice has ceased. They rely on a process of education in which a reckoning with hard truths of systemic oppression lead to national accountability, reparations for victims, healing and potential unity.

However, truth and reconciliation commissions, such as the one in South Africa, are the consequence of decades of sustained struggle and pressure from within and outside the country by relatively small revolutionary organizations, which are often relentlessly persecuted by state forces.

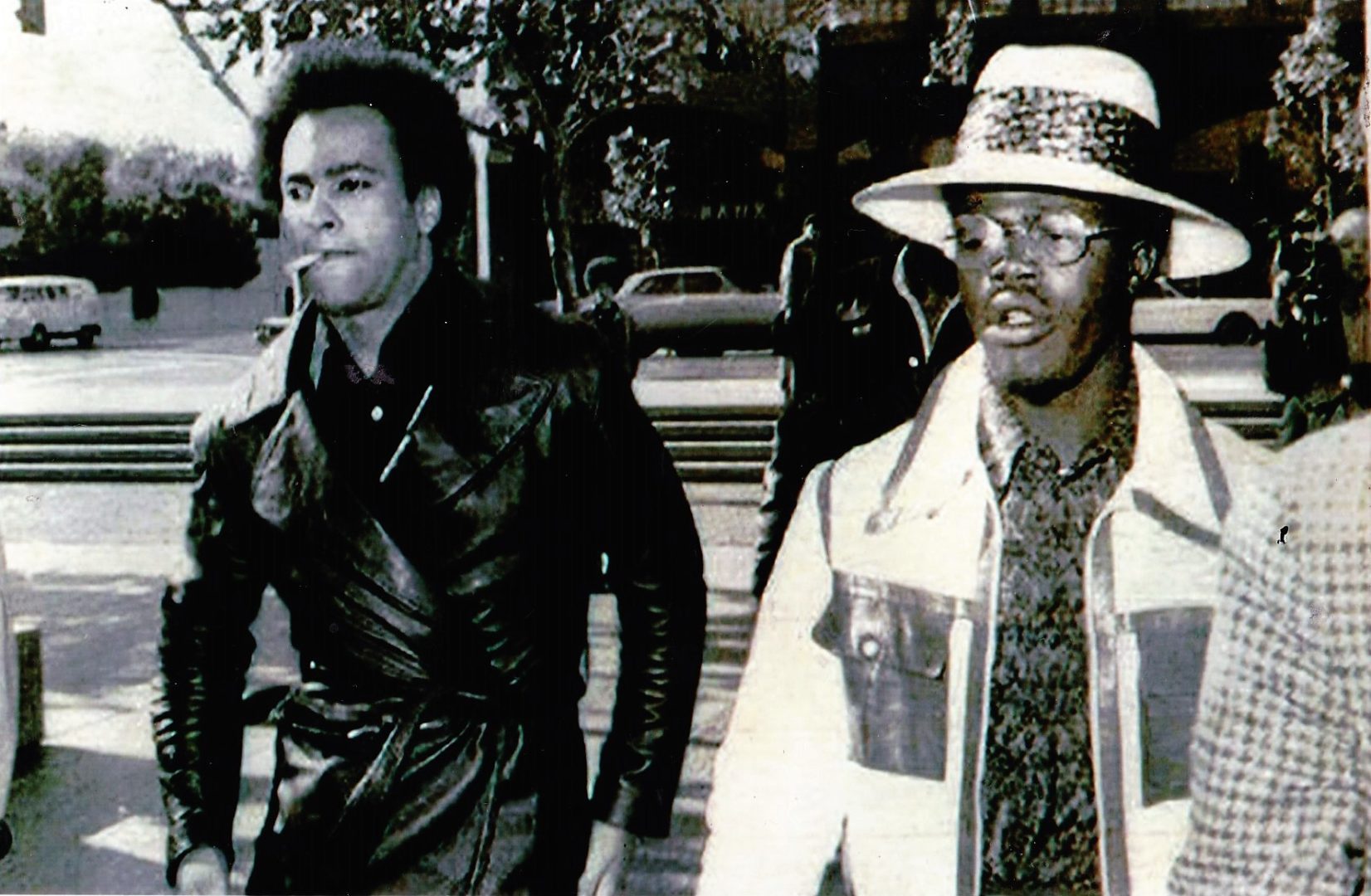

In the following interview, I speak with Black Panther Party (BPP) veteran member, activist, educator and archivist Billy X Jennings who acted as the personal aid to BPP leaders Huey Newton and David Hilliard. Jennings discusses the legacy of the Party within the US and outside it, the role of education in revolutionary practice, his experiences alongside Newton and other Panthers, and lessons for the current uprisings in the United States and the world.

Why did you join the Black Panther Party (BPP)?

Jennings: The circulation manager of the BPP was my next door neighbor so I knew about the Party before I moved to Oakland. I started attending their political education classes and learned of their community programs, which remain our legacy to this day.

How do you feel when you see what’s going on in the streets nowadays?

Jennings: I see it as a prelude to change in America. The present situation reminds me of 1965 before the Selma to Montgomery march, the result of which was the passing of the Voting Rights Act in August, 1965.

The death of brother George Floyd magnified and exposed the ongoing problem in America since its foundation. People are waking up to the fundamentally immoral nature of the system and they’re taking it to the streets. We have a corrupt, racist President and administration who are making things as clear as can be.

Whatever happens, there’s going to be a rise in people’s social consciousness. Protesters are putting their bodies on the line, defying curfews and marching in spite of police. Malcolm X had to go through social struggle to develop social consciousness. Those are young Malcolm Xs out there.

Do you see what is going on now as the fight against the system or as the fight against this one corrupt administration/President?

Jennings: I would take this back to some learning. When I first joined the BPP I read a book called Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung. Mao said that at some point “a single spark can start a prairie fire”. We are seeing the spark in the streets since Floyd’s murder. It could be the beginning of a prairie fire, or not. Out in the streets I see Native Americans, Asians, White, Brown and Black people. I see young and old. This moment has enormous potential.

How do we avoid the kind of repression techniques the BPP suffered, including assassinations e.g. Fred Hampton or the cooptation of the revolutionary struggle by reformists/liberals?

Jennings: Both are very hard things to avoid. For one, the present struggle doesn’t have particular goals. In terms of leadership, there’s no organization leading the protest, an advantage but also a disadvantage. Also, there’s no clear ideology prevailing other than an obscure demand for “justice”.

The movement will have to work itself out. The leaders of this struggle will eventually rise to the top. You will always have opportunists and politicians who will try to play it to their advantage. In contrast, the Fred Hamptons and the Mark Clarks and the Huey Newtons – they are going to be in the community. Only through social practice and leadership will people gain knowledge moving forward.

What would you tell young leaders?

Jennings: I would recommend they read a collection of essays Huey Newton wrote in jail. I realize this is a different day and age; when the BPP formed, arming oneself and protecting one’s community were goals. Now people are less for armed self-defense, and more for “justice” by other means – police abolishment, prison abolishment, reparations, etc.

The whole process right now is an educational one for people who have yet to fully acknowledge and deal with racism and the criminal justice system in the US.

Is there a way to revolutionize the system strictly by non-violent means?

Jennings: I’ve yet to see a strictly non-violent revolution. That said, I don’t think that the American people are ready for armed revolution. Some things still have to happen before that scenario.

As a Black Panther and a Black man in America, I encourage everybody to defend themselves – acquire a gun and defend your family and house. It is lawful. I’m not talking about offensive activity, just self-defense.

How did the BPP address the ongoing issue of Police brutality and racism?

Jennings: The BPP had a proposal in 1970 called Community control of the Police. Our proposal outlined a democratic way of policing and dealt with eradication of racism in the police department. It was a petition which gathered 15000 signatures and placed on the ballot in Berkeley, CA in 1971. Unfortunately, it did not pass with 32% of the vote. Our plan enabled people for the first time in America to choose what type of police they wanted.

The proposal had three crucial elements: 1) it called for a community review board which has the power to hire and fire police; 2) police men and women had to be hired from the jurisdiction they patrolled, i.e. police officers would only come from their own communities, no racist outsiders bringing that attitude with them and; 3) people could file complaints at substations in the community instead of taking a day off work and heading down town.

Veteran BPP members such as Mumia Abu-Jamal and Jalil Muntaqim, remain incarcerated to this day. Do you believe in the abolishment of prisons?

Jennings: Prison abolishment requires a revolution. The US is founded on capitalism. Capitalists won’t change their ways just because we want peace. In practicality, unless there’s a revolution, abolishment of prisons will not happen. The US loves locking us third world people away, as presented clearly in Ava DuVernay’s film 13th.

How does the BPP platform address the struggles of oppressed communities around the world?

Jennings: Racism is a byproduct of imperialism and capitalism. There must be a process of educating people about cause and effect. And that’s part of our struggle – educating people and bringing people to the political level so they can see the problem for themselves and act accordingly.

Information is the raw material for new ideas. Educating and organizing people is the foremost work of every revolutionary and freedom fighter. The BPP newspaper reached a circulation of over 250,000 copies and was one of the most popular outlets in the Black community in the US and the world.

Everything evolved from the BPP ten-point program. The first point said:

We want freedom. We want the power to determine the destiny of our Black and oppressed communities. We believe that Black and oppressed people will not be free until we are able to determine our destinies in our own communities ourselves, by fully controlling all the institutions which exist in our communities.

If people have control of the institutions and governing bodies in their community, they will be free. This simple and crucial principle has been adopted internationally. We had chapters all over the world; New Zealand, Australia, Africa, the UK, and of all places we had a chapter in Israel. One does not have to be Black to be a Panther, it is the principles and the ideals which determine a Panther. So from the get go the BPP was internationalist and one of the many things it resisted was imperialism, which functions like a foot on the neck of all Black and oppressed people. The BPP became an organization that fostered solidarity.

For example, The American Indian Movement (AIM) adopted the ten-point program. If they had control of their institutions and lands the struggle at Standing Rock would have turned out differently.

Provide an example of intersectional solidarity between the BPP and other oppressed communities.

Jennings: The Oakland chapter of the BPP had a profound impact on the 1977 Disabilities act by facilitating and supporting the 504 sit-in – the longest non-violent occupation of a federal building in United States history. Disabled people took over the building in San Francisco for 22 days and the BPP crossed the bridge to provide food every day, reminiscent of our Breakfast for Schoolchildren programs. Brad Lomax, a disabled member of the BPP, led the charge.

Provide an example of solidarity work between the BPP and a liberation movement outside the US.

Jennings: Among many others, the legacy of the solidarity between the BPP and the Palestine liberation struggle goes back to the 60s. Volume 2 of our paper featured the Palestine liberation army struggle. Huey himself went there in the 1980s and met Arafat and other leaders. Palestinians have been part and parcel of the Black and African liberation struggle going on here and in Africa. They are fighting the same type of white supremacist oppression and discrimination we face here.

The BPP Minister of culture – Emory Douglas – frequently featured themes related to Palestine liberation fighters as well as fighters from Africa and Asia in his artwork and in the BPP newspaper.

Is there any point in trying to educate the bourgeois class?

Jennings: Sure there is. All the time. Very few are born with a revolutionary flag flying over their crib.

It’s a process. My parents wanted me to go to college. I had to show them over a period of time the importance of my work. Finally, they started volunteering in BPP programs. My mother was a schoolteacher down in San Diego and she helped out at the breakfast program.

According to the Marxist theory dialectical materialism, material conditions entail contradictions which seek resolution in new forms of social organizing. Meaning, one can be both part of the problem and the solution. That’s what we have to do in America – educate to turn problems into solutions. Revolution is hard work.

Truth is our weapon. When I speak to young people in 7th or 8th grades I bring up a metaphor they all understand – Star Wars. We revolutionaries are the Jedi fighting against the evil empire. And our “Force” is truth. Truth is our weapon and shield. Once you show people the facts and evidence the revolutionary process in their heads begins.

Provide examples of the fruits of revolutionary education and organizing.

Jennings: Education and organizing the people in the community is essential for revolution. When I travel to Oakland, people still approach me and thank me for food or community assistance I provided. Recently, a guy reminded me of how we helped his disabled mother by picking her up and taking her to the grocery store. Those actions may seem trivial and not very glamorous, yet they are what community work is all about.

As a community organizer, you can count on members of the community to help in any way, including hiding you from the police or voting for a particular candidate. Community work is how an organizer earns people’s respect. That’s why fifty years after the BPP is gone, they’re still talking about the BPP.

How did the state try to suppress your own organizing activities?

Jennings: The FBI tried to get me off the street by enlisting me in the military.The government used the selective service as a way of settling vendettas or shipping people away. They used it on other BPP members, and on Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) members beforehand. I had to face off with both the military and the FBI.

When I went to the enlistment center, I threatened I would frag my officers and start a revolution in the military. They decided I was too much trouble for what I was worth. They did not want another Billy Dean Smith. I asked them what’s going to stop them from picking me up off the streets next week and they gave me a discharge letter to carry on my person. My Get Out of Slavery card. I carried it with me for over ten years.

The FBI was another story. They took me to court. I had three choices: fight it, go underground or flee to Canada. I chose to fight my case. At that time, I worked as part of central BPP headquarters personnel. The BPP was under fire. David Hilliard was our leader because everybody was in jail or exiled; Huey Newton, Bobby Seale in New Haven with Erika Huggins, Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver were in Algiers. I served as Hilliard’s aid during his court proceedings related to the April 6th shootout in which Little Bobby Hutton was killed and Eldridge Cleaver was wounded. The trial was on the front page news everywhere in the Bay area. Dr. Benjamin Spock was in court to support David Hilliard. David told him about my case. That’s how Spock became my draft advisor.

In 1971 COINTELPRO was exposed. At this point the FBI arrested me for draft evasion in front of everybody in court. They took me to the San Francisco Federal building and halfway across the bay bridge they stopped the car, and told me they’d throw me off the bridge if I didn’t tell them all the information I knew. Of course I called their bluff. When I went to court my lawyer Charles Garry brought up the fact that he wanted to see all the government records they had on me. But their records included COINTELPRO documents because they were monitoring Huey and David and I was their personal aid. At this point they were still denying COINTELPRO existed, so they had no choice but to drop my case. COINTELPRO saved me from Vietnam.

Huey Newton became public enemy number one in the US. Were you and Newton living in fear of police actions and persecution?

Jennings: Police are paper tigers and bullies just like all reactionaries. You’ll push them, they’ll fall.

In 1971 myself and my best friend Clark were responsible for escorting Huey Newton every day to court as part of the process of his release after appeal. The DA was a guy named D. Lowell Jensen and his lead detective hassled us every now and again – searching us, eyeballing us in court etc. One day the court had recessed early because Charles Garry raised a legal point that the judge had to think about. For me, it was an opportunity to go to the mall and buy a shirt. I jumped in my ’69 Mustang and drove to Macy’s.

It just so happened, the DA’s lead detective had the same thought. I walked around the shopping center and noticed someone watching me. I looked up and saw the detective. He saw me turning red and he ran like hell. I never saw a white man run so fast! He was a big bad macho detective, but when he saw me he bolted. He must have thought Huey sent me to get to him, but I was really there just to buy a shirt.

The next day before court I told Huey what happened and he loved it. The court was packed and as the judge came in, Huey started making a clucking sound like a chicken. The detective heard it, walked out of the session and did not show up for two days. Huey turned to me and said: “That shows you. All reactionaries are paper tigers.”

What are you up to these days?

Jennings: My job is to educate people about the true legacy of the BPP. I am part of a group which formed in 1995 called “It’s about Time”. We put together a website, sponsor BPP reunions and organize exhibits like the one in 2016 at the Oakland museum. I send out BPP material around the world.

Young people out on the streets seek guidance on questions of organizing. I constantly receive all sorts of questions: How did you guys deal with male chauvinism? How did you deal with discipline within your organizations? How do you keep an organization together?

We are from yesteryear yet at the same time we were on the battle lines. Our people were killed and imprisoned. We were the vanguard of the revolution when everyone else ran the other way.

Special thanks to Malcolm X Movement (@mxmovement on Twitter)