It is time to revive the BPP blueprint for a multicultural network of revolutionary groups to confront capitalism, imperialism and racism in the US.

In the late 60s and 70s, the Black Panther Party (BPP) embodied the vanguard of the revolution and anti-fascist, anti-racist action in the United States. The BPP formed an inclusionary, class-based manifesto, promoted armed self-defense and created an array of community survival programs and services, which included a sophisticated educational platform, free health clinics, breakfast for schoolchildren, teach-ins and more. Further, the BPP utilized art and music, via its newspaper and band, to spread its revolutionary agenda.

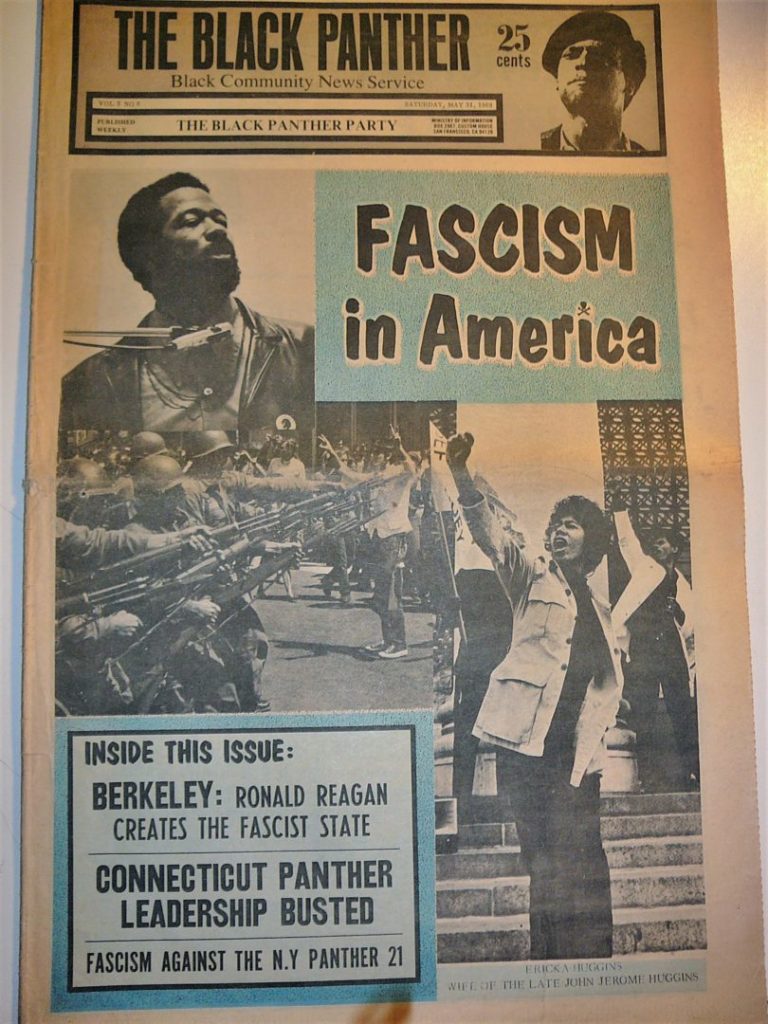

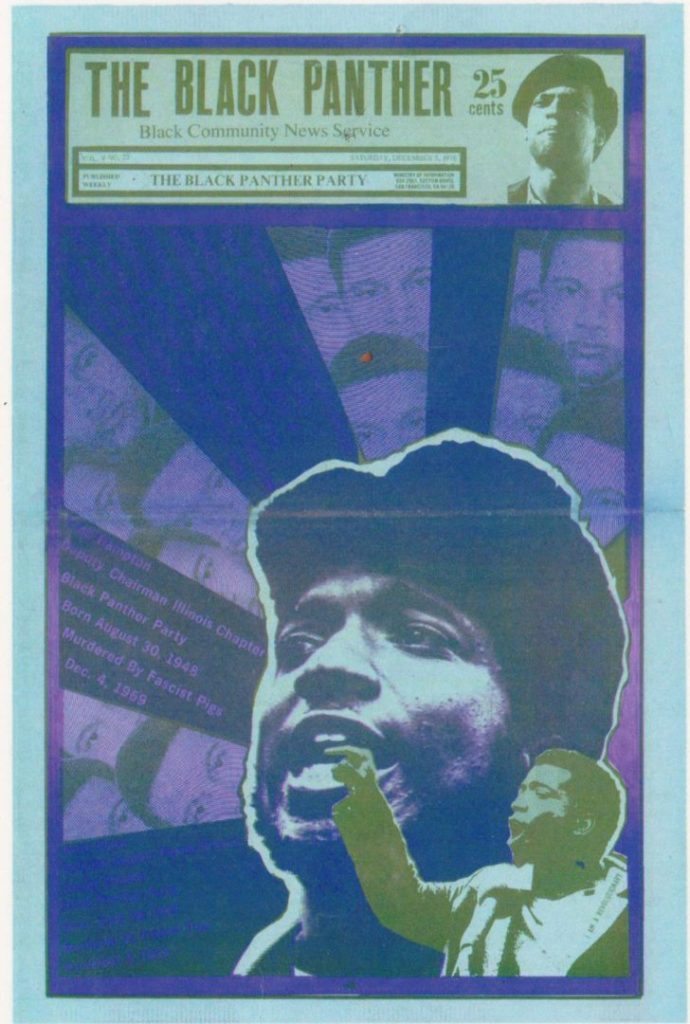

In 1969, the BPP recognized the urgent need for alliances between revolutionary groups to confront the pervasive force of American capitalism and imperialism. In the May 31 issue of The Black Panther newspaper, it published an appeal for:

“…a front which has a common revolutionary ideology and political program which answers the basic desires and need of all people in fascist, capitalist, racist America.”

On July 18-21, 1969, the BPP sponsored a conference, calling for a “United Front Against Fascism” (UFAF); an inclusive, multicultural/ethnic network against American capitalism, racism and imperialism. The conference brought together approximately 5,000 people from hundreds of radical organizations representing Black, brown, Latinx, Asian-American and other marginalized communities, in addition to many white attendees.

The UFAF summit called for the development of National Committees to Combat Fascism (NCCF); a multicultural/ethnic network of chapters under the guidance of BPP leadership as a means of promoting the BPP community survival programs, including Community Control of Police. In 1970, BPP Minister of Defense Huey Newton changed the naming of the NCCF to Intercommunal Survival Committees to Combat Fascism (ISCCF), in line with his theory of intercommunalism.

In the following interview, I speak with Medical Doctors David Levinson and Gail Shaw, veteran members of the first white NCCF/ISCCF in Berkeley, California. Levinson, son of NCCF founders Saul and Cec Levinson, toured and performed as a white member of the BPP’s band The Lumpen, in an example of the anti-racist nature of the BPP. Shaw is the chief archivist at Its About Time — the BPP official archive.

Shaw and Levinson speak on the underexplored and highly relevant history of the multicultural cooperation and anti-racist alliances between the BPP and workers of all ethnic backgrounds, the daily activities of the Berkeley NCCF/ISCCF and its relationship with the BPP, lessons for today’s struggles against capitalism and white supremacy, including the ruthless targeting of the BPP by the state, and the seminal contributions of the BPP in the field of medicine, which have inspired both Shaw and Levinson in their work as physicians.

Yoav Litvin: What is your personal background and familiarity with oppression?

Gail Shaw: Both my parents were first generation in this country. My mother’s family were Jews from Poland and most of them were murdered in Auschwitz. My grandfather came to the US as a young man before the war. My father’s family emigrated from Kiev to America during the pogroms right before the Bolshevik revolution. I grew up in a culturally Jewish household and was taught to always stand up against injustice. My parents backed me up to do what I believed in, even if those were things that scared them.

I was raised in segregated Miami. I remember when I was 6 years old my Russian grandfather came down to visit from NY. He spoke Yiddish and didn’t read English. He was a very friendly, outgoing guy. We walked up to the grocery store in our neighborhood, and I was thirsty. There were two water fountains, marked “white” and “colored,” and he picked me up and I drank from the “colored” fountain. He didn’t know the difference. A stranger came up and started screaming at him. I didn’t understand what was going on at the time — but that was my first conscious experience with racism.

David Levinson: I was born in Brooklyn, New York and grew up in Berkeley, California. Both of my parents were progressive and very politically active. They had been involved in many of the progressive movements in the United States — labor struggles in the 40s, anti-fascist struggles around the time of the second World War, the Civil Rights movement including the Mississippi Summer Project (aka Freedom Summer), the farmworkers struggle to unionize in California and the Delano grape strike and boycott, and activities in opposition to the Vietnam war.

My own activism was a natural outgrowth of the activism of my parents.

My parents were both Jewish. My father grew up in Spring Valley, NY, which at that time was a community of primarily poor and working class Jewish and Black people. My parents always sought to imbue in their children the perspective that Jews historically were an oppressed people and that we as Jews should always act as if we have just come out of slavery, that we should always fight oppression and injustice. My father vehemently opposed the policies of Israel against Palestinians, which he viewed as oppressive and therefore contrary to our history as Jews.

Talk about your activities with the NCCF/ISCFF.

Levinson: Working with the BPP was a family project. My family’s involvement began with my mother who founded the Huey Newton Defense Committee, which organized to support Huey’s defense, raise awareness about his case, and fight for his release. Through this work we became very close with the BPP leadership.

The United Front Against Fascism Conference (UFAF) conference called for the creation of “National Committees to Combat Fascism” (NCCF) to organize concrete programs to oppose incipient fascism.

My family formed the first white NCCF in Berkeley. We were white people working in a predominantly white poor and working class neighborhood. We functioned as a BPP chapter; participating and helping organize in BPP activities, attending BPP political education classes, selling the BPP newspaper and working side by side with BPP members. At the same time, we attempted to develop programs specific to our community’s needs.

We had a community center open 24/7 where we worked and lived collectively and from which we ran a number of “survival programs” in the spirit of BPP. These programs were designed to help alleviate specific community needs and provide inroads for organizing towards a revolutionary transformation of society; a society based on social and environmental justice.

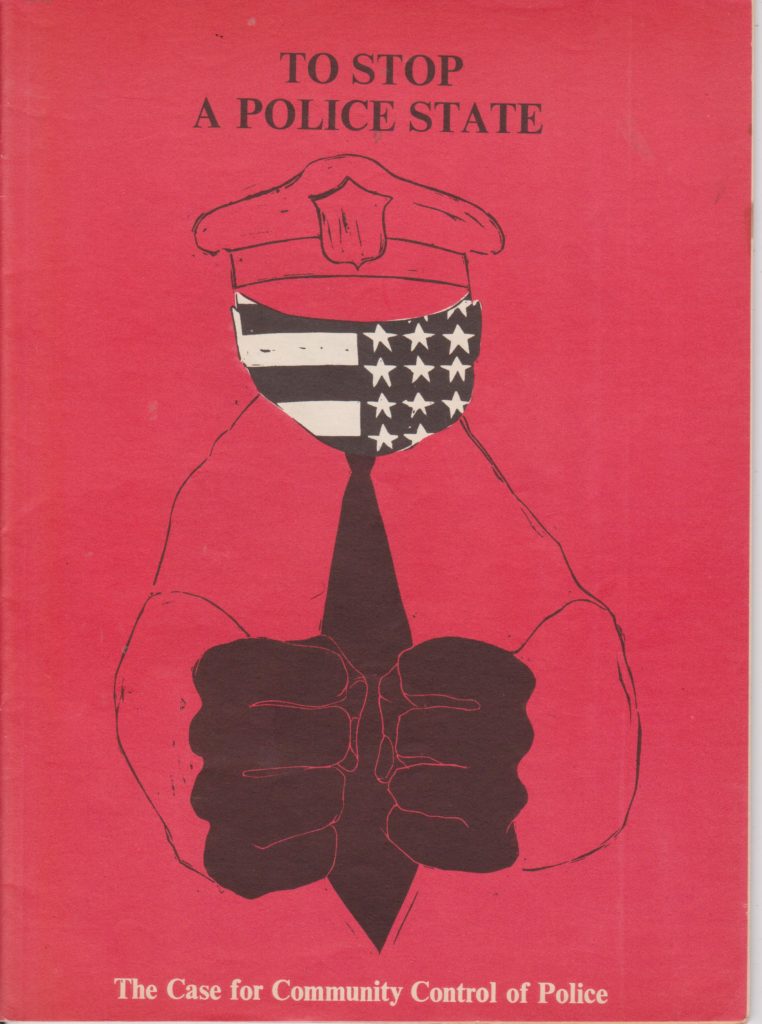

One of the key programs called for was “Community Control of Police”; to place police departments under the control of the communities they were meant to serve as a way of combating police brutality and preventing police departments from becoming tools of state violence.

At our center we had an emergency medical clinic, ambulance service, plumbing and window replacement services, child care, after school tutoring, and community gatherings. All of these programs were free and involved many community members.

How was the BPP portrayed by mainstream media in the US? What was your function as white allies?

Shaw: The media portrayed the BPP as a hate group, a Black nationalist hate group, a danger to white people etc. The very existence of white NCCFs under the auspices of the BPP counteracted this narrative. Plus, the BPP had coalitions with many non-Black groups, for example the Peace and Freedom Party, the Brown Berets, the Vietnam Moratorium group and others.

The BPP organized, defended and uplifted the Black community with a leftist, class analysis, which recognized the common issues poor and oppressed communities faced.

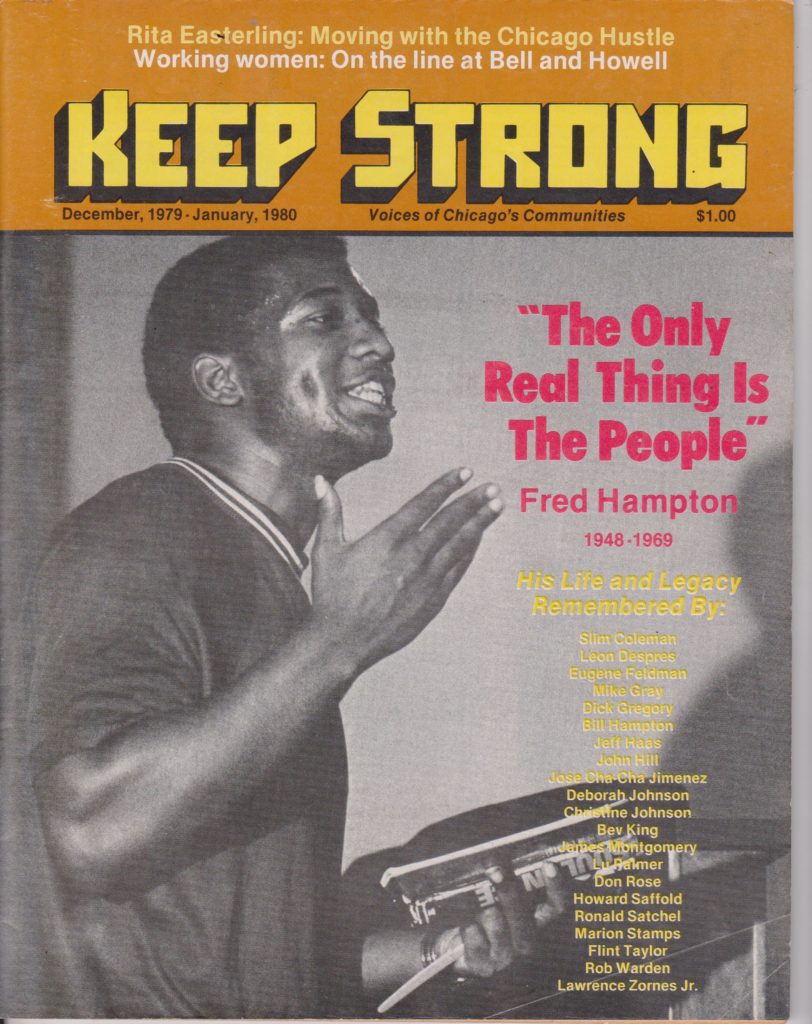

People also do not realize that it was Fred Hampton who started the Rainbow Coalition in Chicago and that Jesse Jackson later co-opted that term. Hampton brought together the Appalachian community, the Black community, the Puerto Rican community and others. The NCCF/ISCCF in Chicago remained active until 1980. In addition to the survival programs mentioned it had a busing to prisons program and its own magazine — Keep Strong.

As white allies, there were places we could go and things we could do that aroused a lot less suspicion. For example — transporting technical equipment to events for defensive purposes.

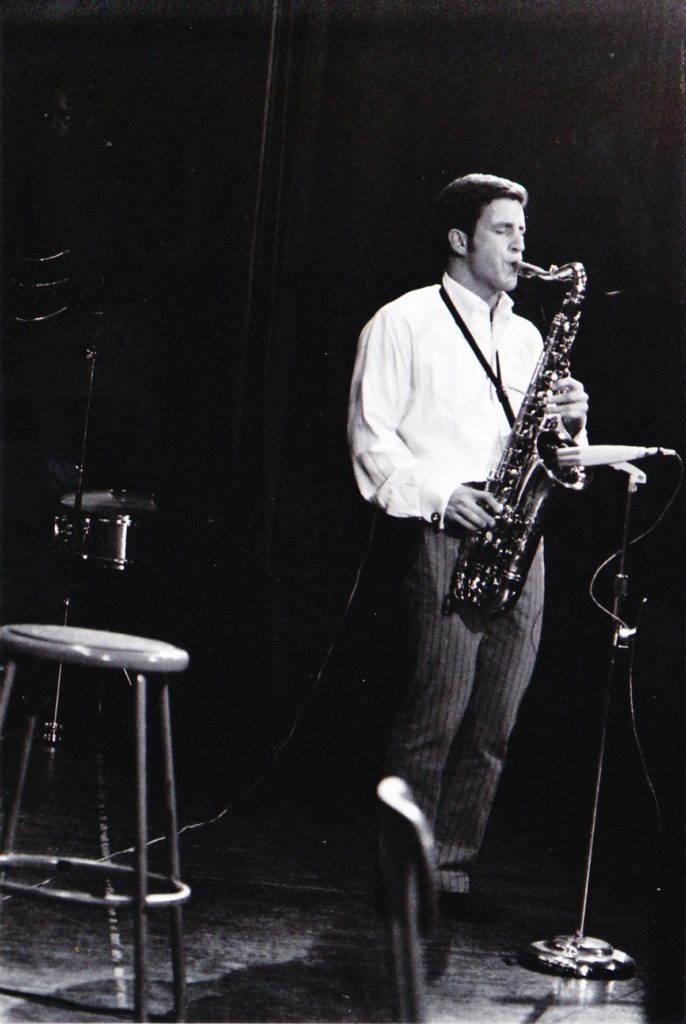

How does your membership in The Lumpen, the BPP’s music band, inform on the party’s ideological anti-racism?

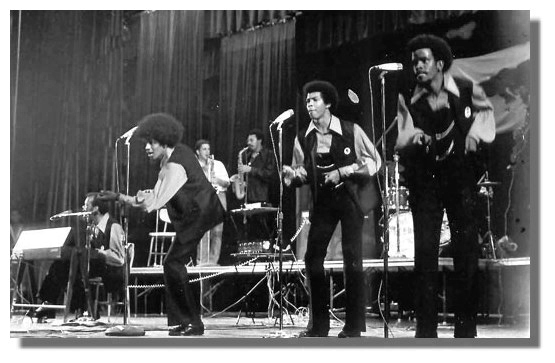

Levinson: BPPMinister of Culture Emory Douglas was the visionary behind the Lumpen and our mentor. He oversaw The Lumpen and was the engine behind the use of art and music as vehicles to spread the anti-racist, class-based message of the BPP.

All of us in The Lumpen viewed our cultural work as a way to help spread the message and the work of the BPP. It was never about personal fame or financial gain. Performing was one of the many tasks we undertook as committed cadre.

I performed with The Lumpen for the duration of the group’s existence. We had a good tight sound and a timely message — directly speaking on the struggles of regular people. We performed in many different venues; college campus gyms, church basements in poor black neighborhoods, community centers, professional clubs and music halls. The Lumpen put an excellent act in the style of the rhythm and blues groups of the time — e.g. Temptations, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles.

During a tour with The Lumpen we were invited to perform at a university in Minnesota by the school’s Black Student Union. There were two white guys in the band on that tour, myself on sax and a guitar player who was hired for the gig. We performed at the school’s gymnasium before a sizeable audience.

During the performance a severe snowstorm developed. We were lodged far from the performance venue and returning that night would have meant driving through the storm in dangerous conditions. The Black student union, which was influenced by cultural nationalist trends at the time, offered The Lumpen and Black members of the band accommodations to stay and wait out the storm, but wouldn’t house the two of us who were white; we would need to find alternative accommodations. The Lumpen members rejected the offer outright and said, “that’s not what we’re about at the BPP. If they don’t stay none of us stay.” We all drove back to where we had been lodged together.

What can leaders today learn from the demise of the BPP? How did the state sabotage your organizing?

Shaw: The BPP underestimated the enemy opposition and how much force they’d turn against a peaceful group trying to elevate their people; organizing communities for self-reliance, providing health care at dedicated centers and education at schools and teach-ins, and helping to feed each other.

I think that some of the things that led to the demise of the BPP and the movement at the time were of course the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) and seeding distrust among people. A lack of trust is one of the easiest ways to destroy a group.

There was constant FBI surveillance and harassment on everybody. It could be 80 degrees out and there would always be two guys in suits and sunglasses parked outside of the house, riding by, taunting. Everybody was wire tapped at the time.

Drugs brought our communities down. The influx of drugs was organized on a much higher level by the government, as described in Gary Webb’s book Dark Alliance, made into a movie called Kill the Messenger. He detailed how the CIA was funding its war in Nicaragua by trading guns for drugs, which basically led to the crack-cocaine devastation of communities of color here in America. Drugs were a huge problem and contributed to the demise of the BPP.

Internally, there also became too much of a personality cult. Also, the influx of drugs became a huge problem in Black and other working class communities. [JL1] [YL2]

How do your efforts inform you on today’s protest movement?

Levinson: It was a very different type of a reality back then, though the issues we faced were much the same as those we face today. The BPP was a disciplined organization with a program, platform and a committed cadre of people which appealed to us. We felt we were engaged in a purpose and agenda. We were not simply reacting to events; the immediate realities of daily oppression, police brutality, economic exploitation and institutionalized racism, but were using our activism for the larger purpose of transforming society and we had a structure within which to do that.

The realities which poor people and particularly people of color face today have intensified. An amazing ferment of reactive energy has come together following the brutal murder of George Floyd and has catapulted the issues of institutionalized racism and police brutality to a national level. These protests have invoked a phenomenal national discourse.

I would encourage younger people who are righteously angered to look at the BPP — not necessarily as a model to be replicated or a perfect organization, but as one piece of history which may have something to offer, an organization with a program and a platform, with the intention of transforming society through concrete actions and organizing.

I also would encourage people to consider the need now for a united front against fascism. I don’t think that the risk of fascism in this country has ever been greater than it is today under the Trump administration.

How did the BPP contribute to medicine in the US and the world?

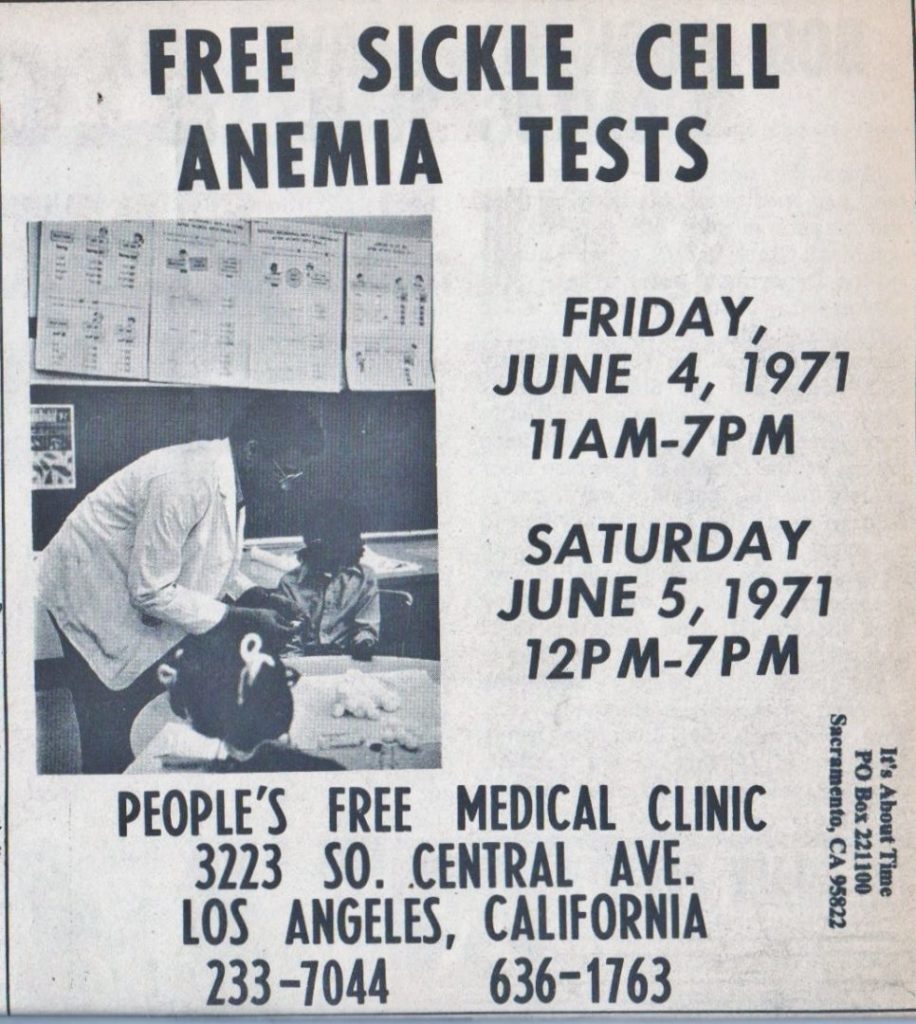

Shaw: The BPP brought public awareness about sickle cell anemia (SCA) through the newspaper and then did widespread testing. Many people, including health care providers, were unaware of this condition. The testing program and increased public awareness led to the government to invest money into research and treatment, and educating physicians about the disease.

The health clinics provided much needed health screening and primary care to under-served areas. Two of them, in Seattle and Portland, were taken over by the counties and are still open today. North Carolina had a free ambulance service because the ambulance companies wouldn’t go to certain parts of town. They got EMT training and were licensed.

Levinson: The BPP viewed health care as a right not a privilege. The BPP was keenly aware of the vast discrepancies and inequality experienced by poor people, and people of color in particular, in terms of access to quality health care. As such several chapters created free health

clinics which were felt to be critical survival programs.

Dr. Tolbert Small is a physician who worked with the BPP. He administered the George Jackson Free Medical Clinic, a BPP clinic in Berkeley, CA.

It was Dr. Small’s vision for the party to create the Sickle Cell Anemia Foundation, which sought to raise national awareness of SCA; a disease which primarily affects Black people and had been largely neglected by the medical establishment. The BPP provided free SCA testing and organized around disseminating information about SCA. This work helped focus national attention and was in good part responsible for the federal government allocating funds for SCA research.

Dr. Small witnessed the use of acupuncture when he traveled to China as part of a BPP delegation in 1972 (I was also part of that delegation). He subsequently studied acupuncture on his own and used it extensively as part of his medical practice. BPP members along with members of the Young Lords Party in NYC created the first drug detoxification center using acupuncture in 1970 at Lincoln Hospital. This work laid the foundation for protocols which developed later using ear acupuncture to help treat narcotic addiction and withdrawal.

On a personal note, our cadre set up a free emergency medical program at our community center in Berkeley. We also had a free ambulance service as one of our community survival programs. I volunteered at the George Jackson Clinic. It was this experience which made me choose to return to college to pursue medicine, for which I was encouraged and granted permission by the BPP central committee.

How can one sustain the revolutionary spirit outside of organizations such as the BPP? How did the BPP affect your personal trajectory?

Shaw: A lot of people who were active with the BPP went into professions crucial for communities, like social work, law and teaching. David Levinson and I both became physicians. There were many who carried on serving their communities and working to support and free our political prisoners. Though there was a lot of repression many people really thrived and learned a lot about organizing and the courage needed to achieve anything you set your mind to. That experience has had a lasting impact on our lives.

Just getting the Black Panther newspaper out every week— national and international news with a circulation of over 200,000 was phenomenal. Remember, most of us were only 19, 20 years old. So much was accomplished by a well-organized group of young people with little resources, the BPP continues to be an inspiration in the struggle for social change and social justice.

Levinson: In anything you do — music, art, medicine, journalism, education — you can be part of a bigger picture of transforming society.

I ended up going to medical school because I was so inspired by the BPP’s free medical programs. I remember going to the central committee of the BPP and asking permission to return to college from which I had dropped out to do political work in order to pursue a medical career. I was encouraged and supported by the central committee. Bobby Seale, chairman of the BPP, told me “we need doctors.”

My experience with the BPP in particular and activism in general has provided me with the center from which I have made choices about my life and in my career as a physician — to try to make what I do part of something bigger and broader. There is power, beauty and humility to work with an underlying drive towards positive transformation of society.

The author would like to express his gratitude to the Malcolm X Movement.

Original HERE.