A Discussion with Professor George Koob on Social Media Addiction

Nowadays, virtual spaces make up a significant portion of the contexts wherein people congregate, share thoughts and discuss ideas.

Social media is a prominent battleground for the hearts and minds of all smartphone users, which in 2017 totalled a staggering 2.32 billion people worldwide. In fact, social media has had a central role in shaping culture and politics, even inspiring revolutions, and by extension affecting the prospects of the human race and our planet.

But in tandem with transforming the human capacity for communication, the replacement of physical with virtual human connections has had a series of negative consequences on society and wellbeing.

In our hyper capitalist reality, interaction in the virtual sphere has been hijacked by an “attention economy” run by the advertisement industry, i.e. private companies use it for the purpose of marketing products. Associated data is appropriated and manipulated for an assortment of nefarious and obscure purposes, as demonstrated by the the recent Cambridge Analytica/ Facebook episode.

In addition to a loss of privacy, a growing and troubling phenomenon of excessive social media usage can negatively affect health and work productivity; extended bouts of online interactions serve as platforms for abuse in the form of online bullying or “trolling” and have been linked to depression, especially in teens. What’s more, the constant barrage of news updates that is facilitated by social media is profoundly stressful for youth.

With the growing awareness to the abuses of media giants such as Facebook and Google, some have called to delete their accounts in protest. However, many have come to realize that they are emotionally dependent on Facebook, Twitter and other platforms. Does that mean social media is an addiction similar to drug abuse? And if social media is indeed an addiction, should withdrawal be a consideration?

To discuss social media abuse, its potential equivalence to drug addiction and possible therapeutic techniques, I spoke with Professor George Koob, Director of the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and one of the foremost global experts on addiction.

Yoav Litvin: What is the evolutionary origin and adaptive utility of the reward pathway? How is it related to behavior and addiction?

George Koob: The reward system mediates positive reinforcement for engaging in life sustaining behaviors, from eating to mating. When the reward circuitry is activated, we learn to attach positive incentive salience to stimuli associated with the reinforcement. This system allows us to adapt to our environments and learn to identify sources of sustenance.

In the modern world, we are surrounded by drugs, such as alcohol, that provide supra-normal levels of activation of the reward pathway, essentially tricking the brain into attaching abnormally high levels of incentive salience to stimuli associated with the substance. This significantly increases the odds of consuming the substance in the future and contributes to the development of alcohol or other substance use disorders.

How would you define “addiction”? Can a behavior such as excessive social media use be categorized as an addiction?

Koob: The term addiction refers to a loss of control over a behavior combined with a strong compulsion to engage in the behavior and physical/psychological discomfort in between bouts of engaging in the behavior. This is easy to see in the context of substance use. Addiction is not a formal diagnostic term and is simply descriptive. For diagnoses, the field uses the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). The DSM-5 recognizes alcohol and substance use disorders, as well as gambling disorder and, perhaps in the future, gaming disorder.

Theoretically, it seems possible that addiction could develop for any behavior that is reinforced. There are now scholarly articles on internet addiction and technology addiction, as well as discussions about including such disorders as “process“ addictions, a term for behavioral addictions that do not involve alcohol or other drugs (terminology of the American Society of Addiction Medicine).

A dramatic deterioration in teen mental health has recently been linked to increased screen time, with a focus on social media use. These findings may be associated with increased exposure to toxic online environments and trolling/online bullying, stress as a result of constant negative news and/or the resulting shortage of real social interactions. Why are adolescents and children more susceptible to the addictive effects of social media?

Koob: Adolescence is a time of intense social learning. To survive in the adult world, it is important for teens to learn how to socialize with their peers. It makes sense that teens would engage in a great deal of socializing, whether online or face-to-face. Research in animal models suggest that the reward system (mediated by the basal ganglia) is more rapidly developed than the executive function system (mediated by frontal cortex) in the brain. Research in teens suggests that an increase in social media use and a decrease in in-person socializing have contributed to increases in anxiety and depression. Studies also suggest that young people can experience withdrawal (e.g., increased anxiety, heart rate and blood pressure) when they are separated from their iPhones during a laboratory study.

Whereas substance use disorders are linked to particular compounds that can be regulated, it is very difficult to limit social media use. Nowadays, 73% of teens have access to a smartphone and therefore to social media. What would be some effective methods to combat the negative aspects of social media use? Would the same solutions available for addicts, e.g. “Social Media Anonymous” groups, work? Can social media be used for positive outcomes?

Koob: It is possible that something akin to a Social Media Anonymous group could help those who spend too much time on social media learn to limit their use. In addition, parents can place limits on access to social media via cell phones and computers with the help of apps, account settings within their cell phone plans, or household policies regarding the amount and timing of use.

Another approach that could help ameliorate problematic social media use addresses a phenomenon known as delayed discounting. Delayed discounting refers to the fact that the perceived value of a reward, such as money or a drug, decreases with the length of time to its receipt. For instance, $5 now is preferred to $5 in two weeks. For those grappling with addiction, perceived value drops more quickly with time than for those without addiction. This increases the sense of urgency to engage in the behavior now rather than waiting until later. Various approaches, such as mindfulness and tasks that improve executive function, have been shown to help people struggling with addiction control their impulses and delay or avoid engaging in the problematic behavior.

While the use of social media can become problematic, research suggests it could also play important roles in helping people grappling with addictions. For instance, social media can be used to identify people at risk of substance use and help people in recovery maintain sobriety. Words used in posts and status updates on social media, as well as words used in posts that are liked by users, can predict with significant accuracy which users smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol or do other drugs. Further, when people in recovery are connected on social media with other people in recovery, posts about pro-recovery behaviors increase the odds that others in the network will engage in healthy behaviors, as well. Researchers are working to identify how best to utlize social media networks to facilitate long-term recovery.

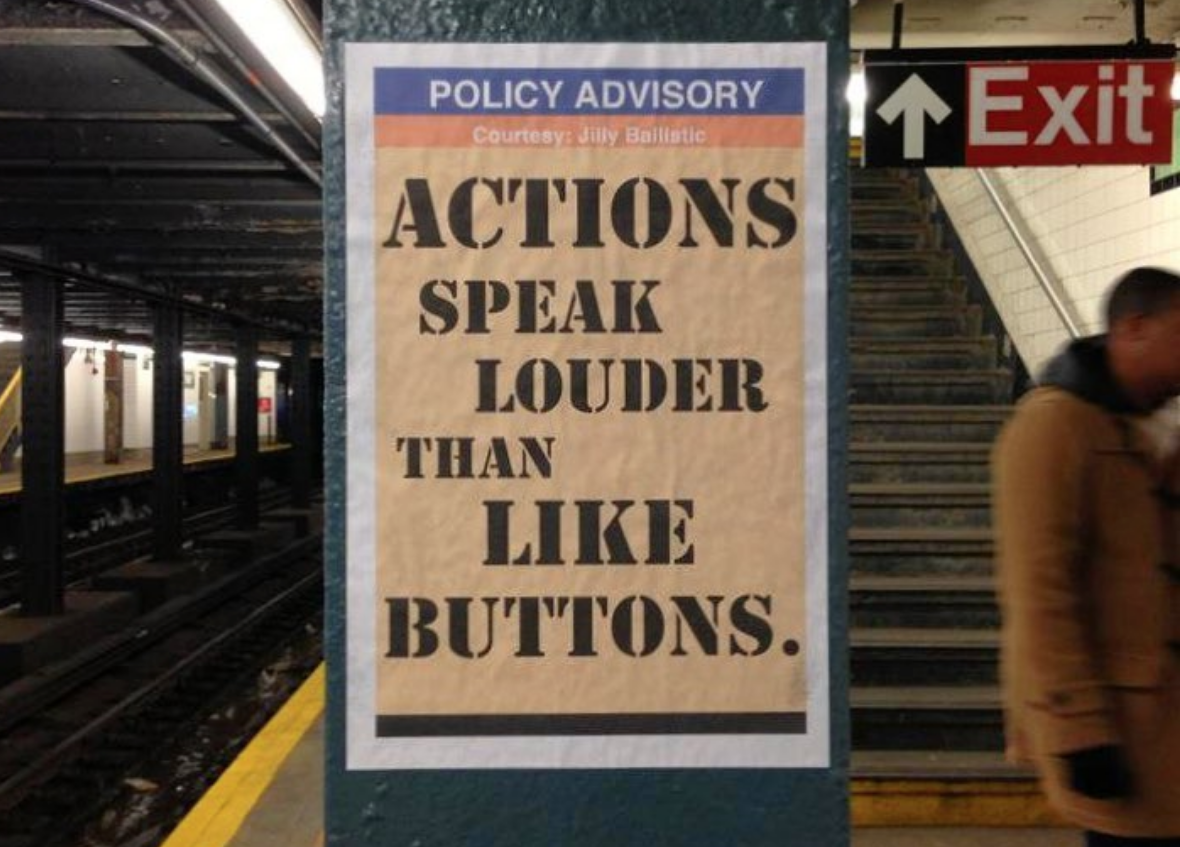

Art and photo by Jilly Ballistic